Diversity: 'When am I going to see the doctor?'

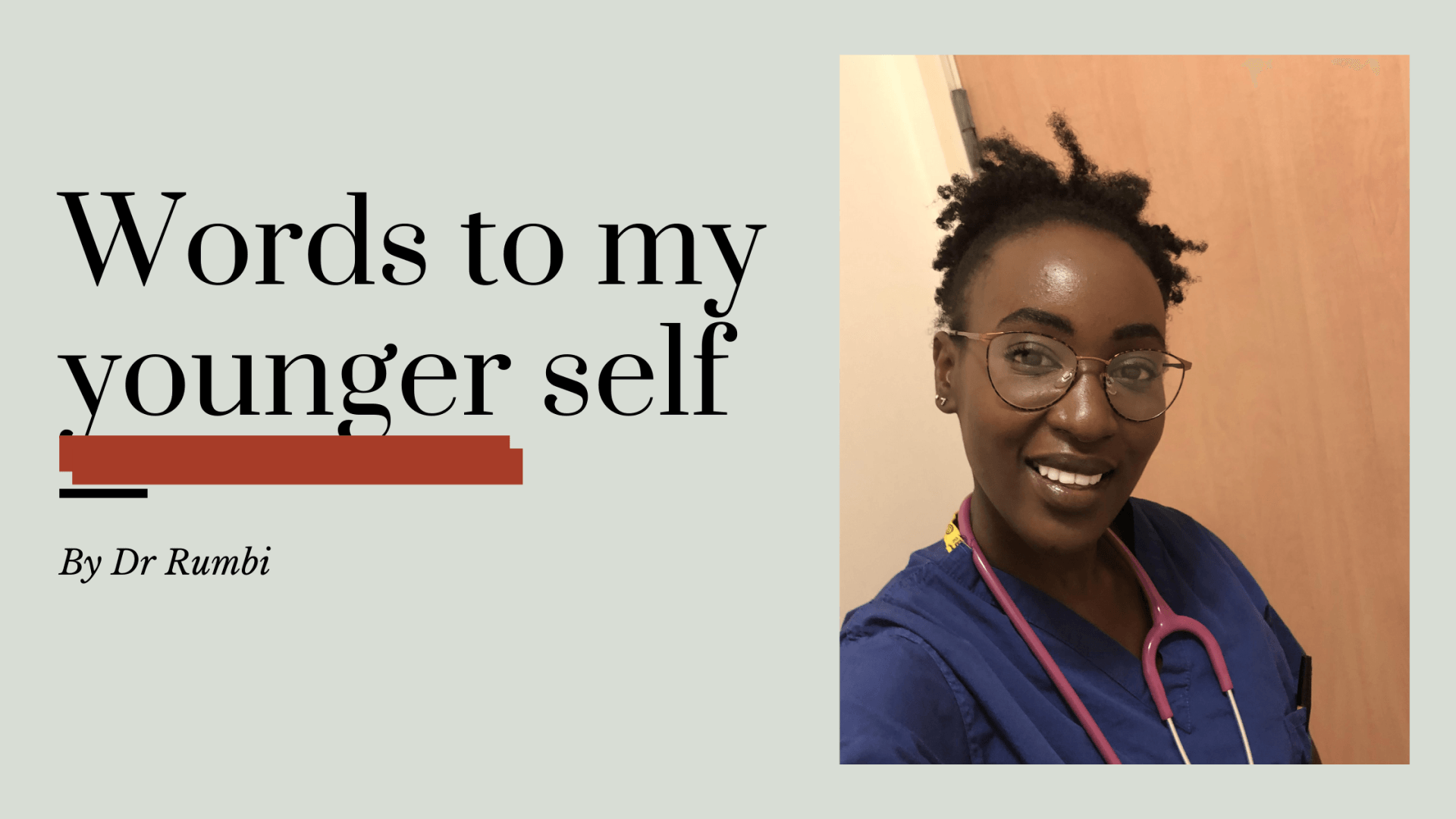

“When am I’m going to see the doctor?” He props himself up in the bed and looks at me expectantly. Internally I roll my eyes. I’m starting to get slightly irritated with that question, and the questions it prompts in me. Is it because I came across as unconfident? Is it because I’m black? Is it because I’m a woman? Is it because I look young? Is it a combination of all these things?

I smile politely and say. “You’ve just seen the doctor” and show him my badge. He goes bright red and proceeds to apologise profusely, “Oh, sorry love, you just look so young...”

Every doctor suffers from imposter syndrome at some stage in their career. To be a doctor, you must be smart, driven, and willing to learn continually. You arrive at medical school fresh faced and eager to learn, probably one of the brightest in your class or your school. Once you get there, you realise you are surrounded by hundreds of other people who are also the brightest and the best. You are no longer easily spotted in a pile of exam papers as one of the high scorers. You might fail your first mock exam and quickly realise that brains alone will not save you this time, it is sheer hard graft for the next 5 or 6 years. Along the way, there may be times where you question whether you deserve to be there, whether you’re good enough.

For black doctors, these questions arise not only internally, but externally too. Black doctors are uncommon, British born ones less so, and ones of Caribbean descent like me, even less.

“Where are you from?” is a question I hear even more often than “When am I going to see the doctor?” Both questions imply, in different ways, the same thing – you don’t belong.

Some would say I’m overreacting, that these questions are asked innocently with no malicious intent and that maybe I should even feel complimented – how nice it is that I look so young and could still be a medical student (if we assume the best as the reason for the question), or how nice it is that someone would be interested in knowing more about my culture. Some might argue that it’s my gender, not my race, that is the main player in this game.

I would disagree. Firstly, the historical and the present day experience of black people, black women even, in this country, give me no reason to offer anyone the benefit of the doubt with these questions. Secondly, good intent doesn’t negate destructive outcomes. Regardless of the childlike curiosity behind levelling ‘where are REALLY you from?’ at every British born brown doctor who you happen to chance upon in Norfolk, or the innocent assumption that it’s unlikely for a young black woman to be your doctor, the weight of the 5th person to ask that question that month burdens that doctor with a feeling of discomfort and upset that they shouldn’t have to bear.

But what

can we do about this?

It seems as though we cannot expect these questions, whether asked directly or implicitly, to die down anytime soon. Although we live in an era of societal change, it will be a long time before the image of the white middle class man– the standard representation of a doctor– is changed in the public imagination.

As doctors we always seek to maintain good relationships with our patients regardless of any obvious prejudices or biases they may have. Black doctors have to accept that especially in certain parts of the country, these questions will be a part of life, and that developing internal confidence and assurance in their abilities will provide armour against these potential micro-aggressions. I have found that maintaining my own professional development, accepting and choosing to believe in positive feedback when I receive it, and finding spaces with trusted colleagues and friends to vent when I need to have been basic but important ways of dealing with this.

I hope that as we to work to diversify the profession, our conversations about race and the politics of being black in Britain continue to spill over from social media into the mainstream. The hope is that doctors, who look like me and share my experiences, will face fewer questions about their ethnic background, or whether we are in fact, doctors at all.

Article written by Shade Henry

Edited by Elina Daitey